The concept of the 10 traditional art forms – known as pan seh myo, or the 10 flowers, and ranging from painting to stone carving – emerged during the Bagan era. While these art forms were once used to decorate pagodas and produce items for the royal family, in modern times they also been deployed to provide souvenirs for visitors to Myanmar.

One of these art forms, gold embroidery, was traditionally used to adorn the clothing of the royal family and others of a wealthy disposition. Today, however, gold embroidered items – particularly tapestries, known in Myanmar as shwe chi hto – are made to adorn homes in Myanmar and abroad. These tapestries are made by placing soft cotton into parts of the base to create a raised appearance and define the shapes, after which parts of the surface are painted and others are decorated with sequins and other objects. For the most part they are not gold, although the string used includes gold threads – the name instead refers more to their colorful appearance. As well as tapestries, the embroidery techniques are used to decorate items such as purses and crowns used in no-vitiation ceremonies.

“At first the world did not know much about Myanmar’s gold embroidered items, ” said Daw Khin Mar Ye, who has been in the industry for 40 years. She runs theThu Zar Hlaing Myo gold embroidery work shop on Mandalay’s 84th street, between 41st street and 42nd streets, which employs about seven workers.

“Even though some foreigners managed to buy our items, most of the time they thought they were made in Thailand. It was only after the Visit Myanmar Year in 1996 that many people realised they were from Myanmar, ” she said.

Mandalay has three large producers, and quite a number of small workshops set up in houses. They sell mostly to souvenir shop owners in sites such as Mingun, Inle Lake and Bagan, where they are popular with visitors from Germany, France and Thailand. Sometimes Thai customers place custom orders by providing the workshop with the image that they want its craftsmen to recreate. Each tapestry takes around a week on average, although larger or more intricate pieces can be much more time consuming.

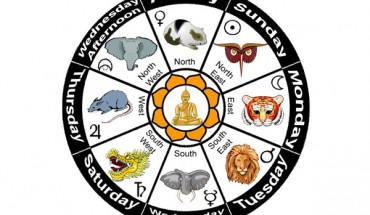

Prices vary significantly depending on the design, size and quality of the tapestry, but a good quality piece can be bought for around 100, 000 kyats. Some customers request that workshops use metallic string instead of cotton, which adds to the price but improves the quality. Tapestries normally come in two styles: traditional and modern. The former show scenes from the Jataka (stories of the previous lives of the Buddha), Ramayana, cosmology and Myanmar history. These traditional designs are particularly popular with foreign buyers. Myanmar buyers tend to use the embroideries in a similar way to paintings, placing them on the wall in their living rooms. A big market is tourism businesses, particularly hotels and restaurants. But times are tough in the industry. The number of large workshops and wholesalers has declined significantly in recent years, Daw Khin Mar Ye said. Local buyers in particular are eschewing traditional art forms for more modern objects. There are fewer orders now and the big workshops of the past are hard to find. We used to have many orders from businesses in major tourism sites and border towns but now they have declined, ” she said. As a result, quality craftsmen are hard to find.

“We’re doing okay because we have built a reputation for quality over the years and have some loyal customers, ” she said. “But it’s hard to make much of a profit on each item you sell. ”

Lann Say Thaw